Whose Freedom Is It Anyway? -- ‘This Fourth of July is yours, not mine’

This Independence Day is being observed against the backdrop of the U.S. Supreme Court setting back women's rights for generations -- just the latest proof that freedom is rarely free.

I have always considered the 4th of July as one of our truly American holidays.

For as long as I can remember, we celebrated with cookouts, fireworks and a grand display of our red, white and blue.

As a Black kid growing up in the ‘60s and ‘70s, I knew my parents worked hard to pursue the American Dream. They moved from the projects of West Philly to the manicured lawns of the suburbs where Independence Day was a big deal. Since it was a big deal for my parents, it was a big deal for my siblings and me. I remember erecting the flag and even dressing up in matching patriotic outfits (I’ve got the shameful Polaroids to prove it).

David W. Brown, Marcom Weekly columnist

It wasn’t until I was an adult when I began to view these traditions a lot differently. I’ve been stopped at gunpoint by officers who swore to serve and protect me. I’ve endured racial slurs by individuals who felt it was their freedom to demean me. I’ve had my house “egged” by those who may have disagreed with the campaign lawn signs I’ve erected – or simply by my very presence in the neighborhood where I’m one of only a handful of Blacks.

So, I find it significant that Independence Day this year is being observed against the backdrop of the U.S. Supreme Court setting back the rights of women for generations. While media attention appropriately has focused on the overturning of Roe v. Wade, it’s simply the latest proof that freedom is rarely completely free.

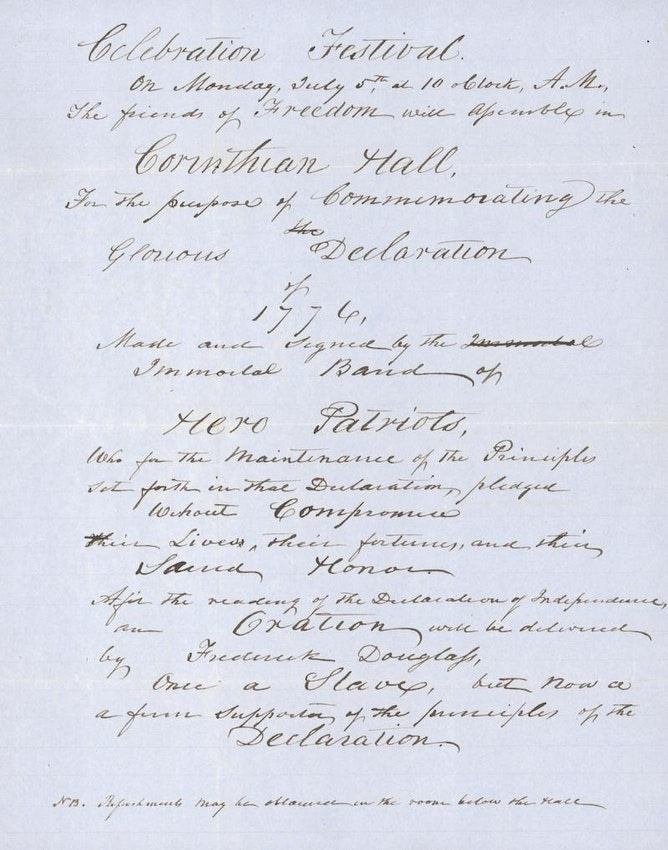

More than 150 years ago, Frederick Douglass, as one of our nation’s greatest orators, posed the question to his all-white audience, “What To The Slave is the Fourth of July?” The year was 1852. The Civil War had yet to be fought, and the Emancipation Proclamation was not to be issued until more than 10 years later. Many in the crowd held slaves, and some even thought Douglass was more of an oddity than the gifted speaker/activist that history knows him to be. Regardless of what those in the packed hall thought of Douglass, he didn’t hold back what he knew to be true in his perspective of Independence Day.

“What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence?” Douglass wrote. “Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?”

It was, of course, a rhetorical question that Douglass was quick to answer:

“I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. — The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

Announcement of Frederick Douglass' speech, 1852

Now, here we are more than 100 years later, and the symbols of freedom still evoke mixed emotions for many of us. While I proudly display the stars and stripes this time every year, I’ve also seen the flag used by others as a weapon — literally and figuratively — to restrict, rather than embolden freedom. Regardless of the symbolism, freedom has always been something that has been fought for—typically by those who have less freedom against those who have more.

Which brings us back to Independence Day, Frederick Douglass and the fight that matters. When Douglass delivered his oration, it wasn’t just a fiery speech to agitate those gathered. It was borne from his lived experience of having escaped slavery, taught himself to read and become the statesman who would play a pivotal role in abolishing the practice of slavery that once held him captive.

For far too many, the chains that bind us may be harder to detect, but their grip is real:

Redlining and predatory loan practices that hold folks back from achieving generational wealth.

Failing schools that lead to poor job prospects, bad life choices and ultimately fuel for the school-to-prison pipeline.

Health inequities that continue to claim Black and brown lives every minute of every day.

So, the struggle continues because it has to. How we live into our freedom determines how much we’re willing to fight for it. For those with the power to grant those freedoms, the battle will be an ongoing one.

Douglass knew this when he wrote, “If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are (those) who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

Let the roar of independence continue to drive us ever forward.